Single Dad Who Adopted Teen Abandoned At Hospital Plans To Save More Kids

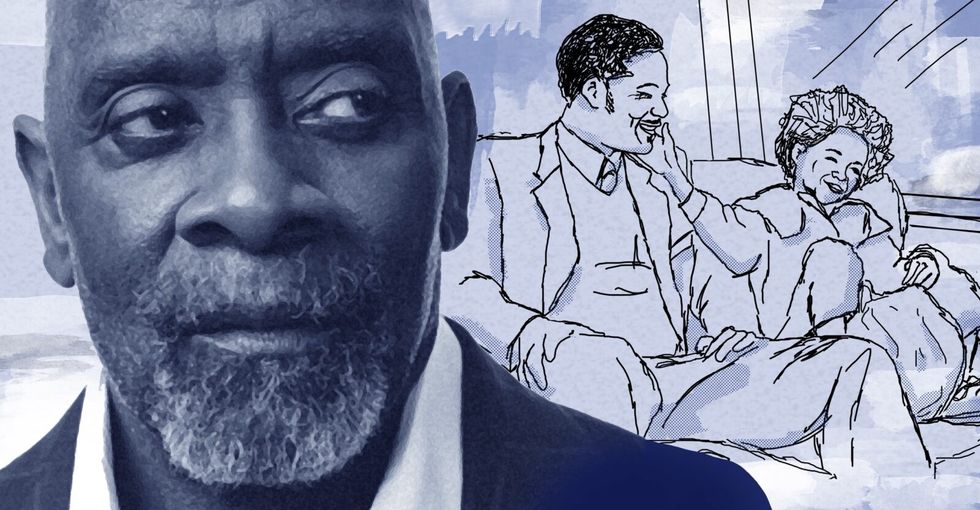

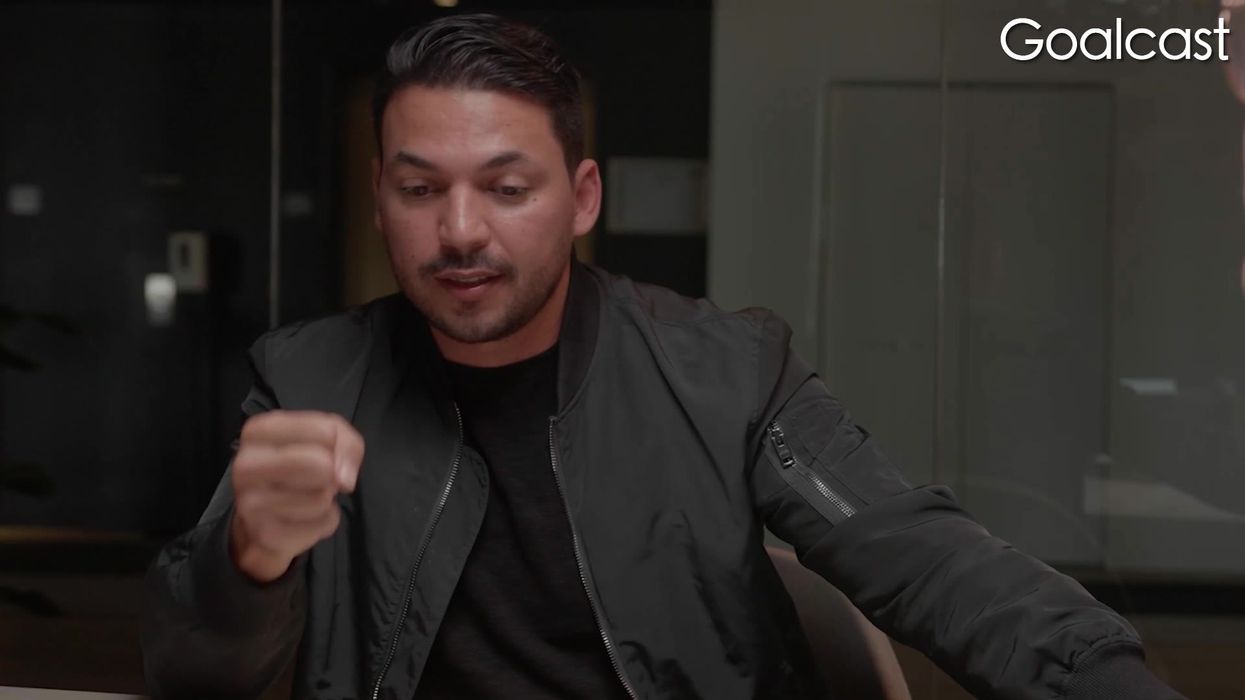

Peter Mutabazi is not your typical dad. After becoming the father of a teen who was abandoned at the hospital, he is on a mission to save more kids.

Peter Mutabazi is not your typical father. The incredible story of his adoption journey went viral at the beginning of the year. When he met Anthony, who was abandoned at the hospital by his adoptive parents, he knew he was meant to be his father.

But there is nothing typical about his journey towards fatherhood, which has crossed continents, cultures and personal trauma. Peter has come out of it with a heartwarming tale that proves that family has very little to do with race, borders or nationality.

If anything, it shows that love really does transcend every barrier, whether they are real or imagined.

From his childhood in Uganda...

Peter grew up in his native Uganda. While today he opens his home to the many foster care children who need a safe haven, he himself had grown up in an unstable environment. In his village, the more immediate concerns of survival meant that people lived from day to day. In their reality, the future was an uncertain, nebulous thing.

And so, parenthood was the farthest thing from young Peter’s mind.

“I did not think about kids. In my background, you’re so focused about what you’re gonna eat in the next hour or in the next 12 hours, that you never dreamt,” Peter reveals. “There was no time to dream or you know, think like somehow you had a better future ahead of you.”

On top of the challenging conditions he lived in, Peter’s father was often abusive to him and his siblings. Growing up in his household meant living through the trauma of his verbal and physical violence but it also inadvertently taught Peter to be responsible before time. The oldest of five, he “had to be a parent at a very young age” to protect his younger siblings from their father’s unpredictable temper.

“If we knew that one of them was gonna get beatings later or we knew that there was trouble, then I knew how to protect them. I knew what to do just in case dad came home.”

That trauma had also warped Peter’s own conceptions of parenthood. “I just couldn’t imagine putting a child in that position,” he thought, at the time. As it turns out, his own childhood gave him a unique perspective into the emotional landscape that foster children lived in. It’s a responsibility that Peter certainly did not take lightly.

“I think what compels me, or what makes me understand them a little bit is that I know where they’re coming from. I know what they felt when someone was not there to say ‘Hey you’ll be okay,’” he says.

“I think that’s why I’ve come to yearning to be a foster parent---to be a dad that would do the opposite, you know?”

...to fatherhood in America

“When I came to the United States, I think I was shocked by the excess of things. There were so many cars, there were so many people, there was so much food you know? I think that was the shocking part,” Peter explains.

The excess he witnessed compared to the scarcity he had lived in for so long inevitably turned into guilt. He remembered where he came from, where the kids in his village and country “would die for having just rice, not beans but just a bowl of rice.”

He also realized that there was a duality to the new society he lived in. While many seemed to enjoy a life of excess, a huge, often forgotten portion of the population suffered from neglect.

“So that’s why for me, the parenting part began to come in because I realized there are kids in neighborhoods, kids in the United States in the foster care system that don’t have anywhere to go,” Peter explains. “Yet the next-door guy has seven bedrooms that are empty....The two dichotomies were difficult to understand.”

As of the latest statistics from 2018, 437,283 children were in the foster care system in the United States, all aged between 0-20 years old. This stark reality meant that Peter could not simply “look the other way.”

Instead, it gave him even more incentive to give back.

Thus began a single foster parent’s journey

Before meeting his son, Peter’s journey as a foster parent was not without its trials. At first, there was the rigorous training, which accidentally ended up being therapeutic.

“At first, I really understood it because they’re educating you on the trauma the kids go through and why kids come to the system and what happens,” Peter explains. “I never got time or someone to help me understand the trauma I went through until I went through the training.”

The process caused a lot of doubts to resurface in him. “My worry was, what if they (childhood traumas) come and they get in the way of me being a parent?” he reveals. “I had a lot of anger towards my dad that I never dealt with. I dealt with it by just forgetting it.”

However, awareness was the first step. “Learning how kids would trigger that, how kids would push the button in your own personal life then you gotta learn how you respond to the kids.”

After completing the training, Peter was still battling against doubt and uncertainty. When he was called at 3 AM to shelter his first child, it all came back to him in full force. He showed the child the room where he would sleep but a myriad of questions assailed him. “Is he breathing? Is he okay? Will he run away if I don’t guard the door?”

In his worry to ensure everything would go well, Peter even slept on a couch in front of the bedroom’s door.

As it turns out, it did go well but Peter especially wants to emphasize the role of friends in facilitating his journey as a parent.

“For me, as a single male I’m really grateful for friends and families that have chosen to say ‘Peter, we will not leave you alone.’”

Eventually, the emotional toll caught up to him

Eleven foster children later, Peter started to feel the emotional toll that his role carried. Imagine becoming a father several times over, but also having to say goodbye to your new child as they inevitably leave your home. That is certainly not an easy thing to go through.

“After eleven of them going back home, I think I felt like you’re crushed into pieces, like part of you has been taken away...Because you love and care for them and part of you is saying goodbye,” Peter recounts.

So after the eleventh child, Peter was emotionally done. When they called him about Anthony, he had said goodbye to a child only four days before. So, he came up with a set of conditions, to ease the task.

“When he came in, I was determined not to know him personally, not to know anything detailed of his past, because I was afraid I would get attached and then he would be gone.”

Anthony came in at 3 AM but this time, when he called him “dad,” he told him “you can call me Peter.” But Anthony insisted and asked, “Can I call you dad?”

(You’ll see why this little moment was almost prophetic.)

Anthony’s stay only lasted two days, so Peter thought he was very safe from the risk of getting attached. But the opposite wasn’t true: Anthony almost immediately saw him as his dad. “I think for him, he jumped to me as a ‘dad’ quicker than any kid I have had before.”

When the social worker came to pick up Anthony two days later, Peter allowed himself to ask about the kid’s backstory, knowing that he would not see him again. What he learned next struck a chord deep within him.

Anthony had been in the foster care system for a year and half. He was then placed in a family that adopted him at the age of four. That same family had just dropped him at the hospital and abandoned him there.

“I had run away when I was little. I had no one, nobody in my life to even look for me to make sure I was okay,” Peter remembered. “Nobody. And I could not imagine this kid going through the same thing I went through. I could not imagine having a kid for 9-10 years and just letting him go.”

He immediately changed his mind. “I said, you know what? I will take him,” he told the social worker.

“And as I was saying I would take him, I knew I would be his dad because he had asked me if I could be his dad. From that point, I knew ‘Well, he has nowhere else. No family needs him. So I can be a dad. The kid knew ahead of time that I’ll be his dad.”

An unconventional family that works

The thing is, there is nothing conventional about Peter’s family. When he first applied to be a foster parent, he “was worried of being judged” or that “the kids would not accept me because they would prefer a female maybe in their home.”

As it turns out, being a single father actually filled a special place in these kids’ lives.

“Me being a male was probably the one thing they wanted, that they lacked where they came from,” Peter reveals. “I think most of their parents were either single moms or their foster parents were females. So I could tell they really longed for a dad. They had me and I could do the boy thing and they could relate to me.”

However, becoming the father of a biracial family was not without its challenges. As America is still coming to terms with its treatment of its black community and other minorities, Peter’s family represents a powerful symbol of unity. But his experiences also speak of the realities he has to deal with.

Abuse and neglect don’t discriminate, Peter reveals, drawing from his experiences as a foster parent. Out of the 13 kids he has taken care of, seven of them were caucasian. The difference was felt more in his approach to parenting. With the black kids, their identity was often the object of attack at school so Peter had to find ways to guide them through these negative experiences.

“With the white kids, it’s me trying to teach them what my life is like...One thing they did have is their dad is different. Their dad is seen as different than they are,” he explained.

He’s not worried that his kids would be discriminated against at school. “I am not fearful that my kids would be treated differently at a Walmart. I am not afraid that my kids, when they go to the store or the mall, that somehow they’ll be seen as different. No, I don’t have that.”

Instead, he has to teach them how discrimination affects him, and “help them understand, that person is nasty just because I look this way, because your dad is black.”

These incidents are a part of their daily lives. Peter recounts how, at the airport, he always gets stopped before boarding to be asked additional questions while his son gets to pass through without any issue. To Anthony, it is irritating that somehow they can’t recognize that Peter is his dad.

Then I have to sit with him and say ‘Anthony, yes I’m your dad but some people don’t see me as equal as any other dad because of my color.’

In his parenting, Peter makes sure to highlight that the discriminatory treatment he receives is not unique to him but that many other black people and people of color are facing similar issues. In a sense, because it is happening to someone they love deeply, Peter’s kids have a unique perspective into the workings of discrimination.

That’s something they also have to keep in mind. As Peter tells us, his kids have to be careful when playing with toy guns--if they bring them into the car with him, it might put Peter’s life in danger. If he goes for a run in fancier neighborhoods, his kids come with him just in case.

“I’ve also told them that if the police stop us, get your phone and start recording. It doesn’t matter what it is, just get the phone and record because we don’t know what the reaction is gonna be…He can protect me when I am unable to protect myself.”

It’s a difficult position for a child to be in, Peter reflects, but it is unfortunately part of the reality of existing as a black man in America.

How Covid-19 expanded Peter’s family

During the lockdown, Peter got a call from a social worker about a 7-year-old who had nowhere to go. At first, he was indecisive, fearing for their safety in the midst of a pandemic. But then, he listened to his heart and knew that he had to open his home, especially in such a difficult time.

In this case, quarantine has worked in his favour. Since daycares were closed, he “had an opportunity to have him every day.”

“The bonding was quicker and easier. We were with each other at all times. And also, it was easier to deal with the trauma of separation, the trauma of not having parents and all that because there was an adult 24/7 for him.”

Peter got to learn a lot about him fairly quickly, so the new kid bonded with them quickly because they could not go anywhere. Mostly, it was great for Anthony too.

“It was good for him to have another human being who plays the same video games but that he can talk to and feel like he has a family as well. For me that was absolutely wonderful.”

The experience also helped Anthony to remember where he’s come from, which as Peter says, would mean that he would be able to help others dealing with similar pains and traumas. It has taught him how to be responsible for someone else but also to appreciate his father’s efforts, now that he gets to experience the difficulties and joys of fostering a child as an integral part of the process.

He learns from them every single day

“As a kid, I was never told any positive thing. As a kid, I was never touched. I didn’t get any physical touch from my parents. In some way, I have never been a kid in my life. Like I can’t remember the last time I was a kid,” Peter admits.

When he became a parent, he also got back in touch with his inner child simply by taking care of his children. “I am not a huggy person but sometimes they’ll come and ask ‘Can I have a hug?’...I remind myself, ‘Hey, I needed it as much as they needed that hug,’” Peter realized.

They’ve also taught him the value of small moments, like reading them a book before going to bed, which was less about the story and more about spending that time together. On a deeper level, being a parent has also forced him to come to terms with his anger issues. The more time he spent with them, the more he was able to learn how to manage his emotions and responses.

A full-circle journey

As for Uganda, Peter is planning a trip there soon with Anthony, providing Covid-19 allows it. For him, the journey back is significant in many ways. After all, that’s where his story started.

“To go back home...and show my people that you can be a dad, it doesn’t matter to who. My mom used to say ‘You can have a house but house two people but your heart can house a thousand people.’ That’s what I’ll like to do as well, to go show him where I came from.”

He also wants Anthony to be loved by his family back home, “because he’s never had that.”

Now I Am Known, a project for the unseen and unheard

Back in Uganda, after he ran away from his village, a man had taken him into his home. This benefactor gave him an opportunity to be known, as Peter explains. He made him believe in his potential and was pivotal to Peter’s inspiring journey.

“I didn’t have someone to encourage me. I didn’t have anyone to ask me to dream. I didn’t have anyone to really guide me in some way. I always felt I was nobody. I always felt no one cared about me.”

Drawing from his own experiences, Peter decided to create Now I Am Known, a project that will aim to “make the unknown, known.” It will provide a voice to the people who feel like they’re not seen or heard, and “give them an opportunity to say ‘We are known.’”

“It will give an opportunity too to someone who wants to make a difference, wants to give an opportunity for a child to be known, to say ‘Yes, I would like to be a part of this movement or I would like to do something for a child so they never have to feel that they’re not known.’”

You can sign up to receive updates on Peter’s exciting projecthere and be a part of his efforts to shine the spotlight on those who deserve to be seen and heard too. Together, we can uplift those who need us the most.

woman speaking to another woman sitting opposite herWestpac Banking

woman speaking to another woman sitting opposite herWestpac Banking elderly couple laughing and drinking coffee outside a restaurant

elderly couple laughing and drinking coffee outside a restaurant