Woman Experiences Full-Blown Panic Attack - A Stranger Takes Matters Into His Own Hands

Stranger Helps Black Woman Having Panic Attack on Flight

Flying is a great way to travel. It's quick, you get to sit back and relax while someone else does all the driving, and you get to travel to places you may otherwise never see.

Yet, for many of us, flying comes with some unwanted baggage: also known as crippling anxiety and all-out terror. After all, hurtling through the air at 38,000 feet in a metal tube can be daunting (to say the least).

For one young woman, a recent flight had her anxiety soaring to new heights...and then a kind stranger stepped in.

A Stranger Helps Out a Fellow Passenger

from MadeMeSmile

In a Reddit post that has gone viral with over 29,000 upvotes, the original poster (who posts as @narrow_ad_2695) recounted what happened on a recent flight to New York City.

"On a flight into NYC today. On the left of the aisle was a young Black woman. On the other side of the aisle an older white guy. They were traveling separately."

As the plane was coming in to land, it hit some turbulence. Which, for even the most seasoned flyer, can cause a flutter of anxiety.

For this female passenger, however, her anxiety went immediately to Defcon 5, plunging her into a "full-blown panic attack." For anyone who has never experienced a panic attack, they're no joke. The intense, overwhelming sense of fear and dread triggers severe physical reactions, including palpitations, sweating, chest pain, dizziness, and difficulty breathing.

Seeing her distress, the stranger "reached across the aisle, tapped her gently on the shoulder and asked if she was ok."

She was decidedly NOT OK.

By this point, her thoughts of certain impending doom had completely and utterly annihilated any rational thought that may have been trying to take up space in her brain.

"She turned to him and grabbed his hand so tightly, tears streaming down her face," the OP wrote. "She said, 'I can't do this' and he calmly said, 'We're going to be fine. You'll see.'"

"The man just let her grip his hand all the way until we landed."

To have someone reach out and say it's okay meant the entire world at that moment. According to the OP, the woman was able to calm down and get through the rest of the flight. Once the aircraft landed, she "grabbed his hand with both of hers," and thanked him for being there.

"In a country where it feels pretty divided, this was just a wonderful moment to witness."

The Power of Real Human Connection

It's no secret that the United States is rife with political, social, and cultural divisions. From contentious elections to polarizing social issues, the country is grappling with an ever-increasing divide, leaving people feeling disconnected and uncared for.

And, let's face it, it's not just a US problem. Globally, we're not doing so great either. But it's stories like these that remind us that kindness and connection still exist in the world.

"I'm not sure why, but this made me cry. Some people just come along and restore your faith in humanity," one commenter wrote.

Another commenter wrote, "This is what being a good human looks like. It doesn't matter race, religion, or creed. Just be a good person. We're all on the same ride and need help here and there."

And then there was this comment, "I was recently stuck at a small airport with about 50 people, maybe more. The lady sitting next to me quietly called a nearby pizza place and ordered a bunch of huge pizzas for everyone, including TSA. Sometimes ordinary people do extraordinary things." For real.

So often, it can feel like we are all alone in our struggles, that no one else sees what we're going through. But sometimes, someone comes along who truly sees us.

And instead of turning a blind eye, or walking away, they join us in the dark and just sit with us. Reminding us that we are not alone and reassuring us that we will get through it.

By meeting his fellow passenger where she was and simply being present with her, this man turned a terrifying experience into a beautiful reminder of the power of extending a helping hand.

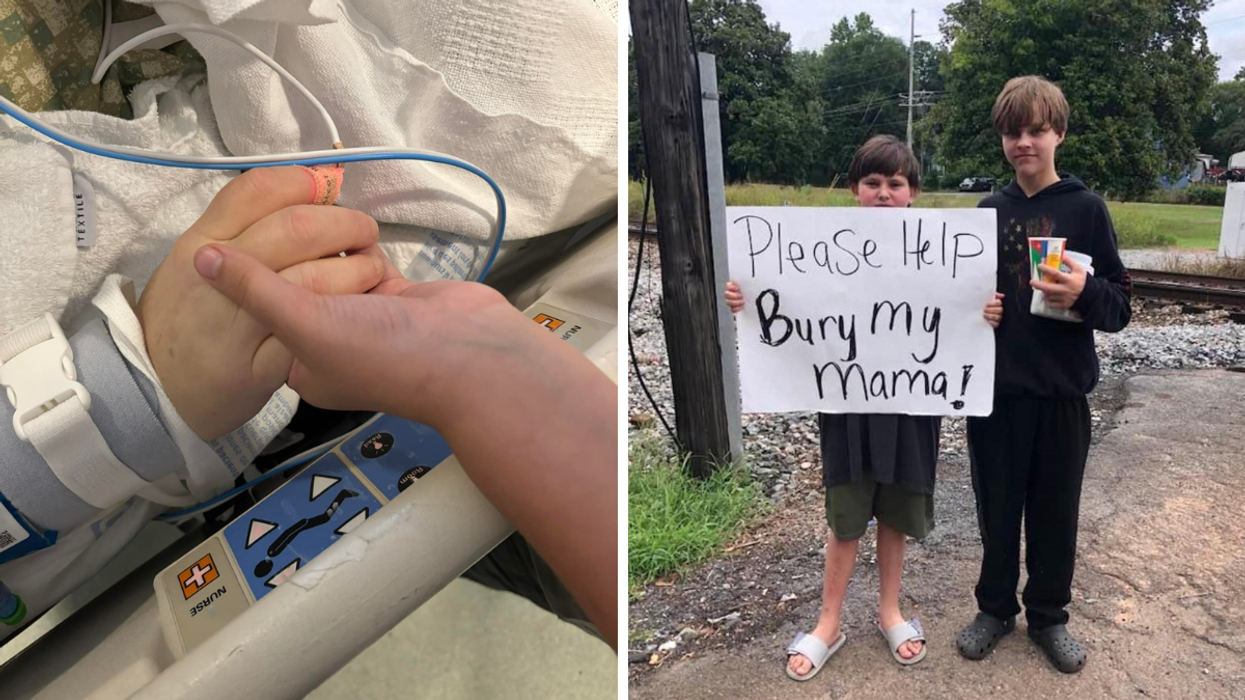

Donate to Help 11 year old Kayden bury his mama, organized by Jennifer Grissom

Donate to Help 11 year old Kayden bury his mama, organized by Jennifer Grissom